|

|||||||||||

| Previous | Next | ||||||||||

The family legend says: They were Anabaptist (Mennonites) and left Switzerland because of religious persecution, and moved to Vlissingen and Amsterdam, where they engaged in the ship building trade.

Zeeland (Vlissingen) and Holland (Amsterdam) were the two most flourishing provinces in the Netherlands. The other provinces were agrarian and were not exposed to all the coming and going of the maritime provinces. We actually have no way of knowing how the family happened to pick working on ships except that it was the largest industry around in both provinces. It is possible that they were carpenters in Switzerland. Regardless they picked or lucked into the profession that was one of the highest paid in the Netherlands. They would have been making 30 to 48 florins per month. By contrast, a house carpenter would have been paid only 15 to 16 florins each month and a captain in the Dutch Navy was only paid 30 florins per month.

It is also possible that in the position of working on building ships that they also invested in the shipping industry. A characteristic feature of the Dutch seaborne trade was know as the “rederij”. This was a flexible type of co-operative enterprise in which a group joined together to build, buy, own, charter or freight a ship and or its cargo. The individual “redes” would contribute capital in varying amounts and share in the return on a percentage split. The redes would range all the way from wealthy merchants to dock hands. A contemporary writer estimated that only about one ship in each hundred was operated in any other way than that of the rederij. Such a system of joint ownership eliminated that chance of one person losing so much money if the ship was lost. It also insured that all the various people involved would be checking to see that all was going according to plan and that the labor, material etc. were of the quality and quantity needed to make a first class operation. The other very important side effect was that such a system tended to integrate the life of the town with that of the maritime community. (Any discussion of the Netherlands of this period much relate largely to the Maritime World since in those years Zeeland and Holland became the largest sea trading empire in the world.)

By 1543 Emperor Charles V of Spain had brought all the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands under his rule. This had been accomplished by marriage, accident, and force when necessary. The ten states of Holland sent a petition to Charles V outlining the necessity of sea trade to the survival of the Netherlands, particularly of the Maritime Provinces. The petition in part read:

“It is noticeably true that the provinces of Holland is a very small country, small in length and even smaller in breadth, and almost enclosed by the sea on three sides. It mush be protected from the sea by reclamation works, which involve a heavy yearly expenditure for dykes, sluices, millraces, windmills and polders. Moreover, the said province of Holland contains many dunes, bogs, and lakes which grow daily more extensive, as well as other barren districts, unfit for crops or pasture. Wherefore the inhabitants of said country in order to make a living for their wives, children and families, must maintain themselves by handicrafts and trades, in which wise they fetch raw materials from foreign lands and re-export the finished products, including diverse sorts of cloth and draperies, to many places such as the kingdoms of Spain, Portugal, Germany, Scotland, and especially to Denmark, the Baltic, Norway, and other like regions, whence they return with goods and merchandise from those parts, notably wheat and other grains. Consequently, the main business of the country must needs be in shipping and related trades, from which a great many people earn their living, like merchants, skippers, master pilots, sailors, shipwrights, and all those connected therewith. These men navigate, import and export all sorts of merchandise, hither and yon, and those goods that they bring here, they sell and vend in the Netherlands, as in Brabant, Flanders, and other neighbouring places…”

It would appear that the Dutch had taken over most of the trade which was formerly held by the Hanseatic Cities. Due to the Dutch being more efficient they had been able to offer lower rates than the Hanseatic League. One would have thought that the Eight Year War would have curtailed trade, but to the contrary; trade really boomed.

This may seem strange but in those days wars were conducted with a more practical eye. The world was too dependent on trade, and if the war was causing too much inconvenience, they just slacked off the war for a bit—all in all a rather civilized way to have a war. The Eight Year War was in most cases a boom to the shipments of grain, timber, wine, herring and other fish. This boom gave the merchant rulers of the cities cause to join with the maritime world and become a political as well as an economic power.

Various leaders such as William of Orange tried to form a State in which Protestants and Roman Catholics could live together. The problem was that his Calvinist supporters were not about to buy such an idea. They, the Calvinists, were having enough trouble trying to put up with the various Protestant minorities. The Roman Catholics were not going to be tolerated. As soon as a Roman Catholic town surrendered to the Calvinists, the town council was filled with Calvinists and the Roman clergy was chased out of town.

One of the big events of the Eight Year War was when General Parma captured Antwerp in 1585. He offered the Calvinists who would not convert to Roman Catholic a two year period during which they could move themselves and their goods from the city. This is another example of a religious forced move that crippled the economy of the area they left. Unfortunately their connections were such that the business went with them when they left Antwerp. It was really Amsterdam that gained in the move. Not all the people who left Antwerp were wealthy merchants. The skilled artisans, the expert craftsmen as well as casual laborers were part of the exodus. The result was the population of Amsterdam increased some 75,000 people within a twenty five year span.

It is in these years that Dutch trade expanded to the point that the Netherlands became know as the Seaborne Empire. Trade was carried on from Brazil to Africa; Indonesia to Japan. The formation of the East India Company and the West India Company was during these years. It is important to note that the latter Company paid at least a 12% dividend for the next 198 years.

By 1648 the Dutch were indisputably the greatest trading nation in the world. Their commercial ventures were not all securely held by any definition but they were returning an encouraging profit. Their achievement in European trading makes impressive reading. C. Wilson writes:

“they had managed to capture something like three-quarters of the traffic in timber, and between a third and a half of that in Swedish metals. Three-quarters of the salt from France to Portugal that went to the Baltic was carried in Dutch bottoms. More than half the cloth imported to the Baltic area was made or finished in Holland. All this in addition to the fact that they were the largest importers and distributors of such varied colonial wares as spices, sugar, porcelain, and trade-wind beads…”

With the town councils ruling the areas, the final result was that the Dutch Republic was actually ruled by an oligarchy of about ten thousand people. They controlled all the important offices—hence they controlled the state. The best description is that they were allied rather united. They argued and scrapped among themselves and only became united when an outsider appeared to threaten them. In the final analysis it was the upper middle class businessmen who ruled the country.

The Calvinists thought they had founded a nation with God’s blessing and with His active support. They still looked at their Roman Catholic fellow country men with a jaundiced eye. They considered the Roman Catholics as second class citizens and as potential traitors. The Calvinists also looked askance at the various protestant minorities such as the Anabaptists/Mennonites. Fortunately for the Myers family the Calvinists were too busy with their battles with the Roman Catholics to pay much attention to the Mennonites.

But above all, trade, not a crusade, became the word of the Dutch. They had wanted to control Brazil, and they had wanted to destroy Spain. They had wanted to eliminate Roman Catholics in Holland, and they had hoped to re-conquer the Southern Provinces. But security, freedom of trade, and toleration as long as it led to stability became much more important. It may be called a lack of chauvinism that led to much of their success. Their loyalty was to a city state or at most a province rather than to a dynasty or a country.

Living conditions in Holland during the years the Myers family lived there were not always the best. Until the time the family left for Pennsylvania most of the houses were built of wood and clay. Stone and brick houses were only for the rich. In the first half of the 17th century, houses in the maritime provinces were said to be two to three times better than housing in France. It would appear that the Dutch burgher and his wife were more proud of their house. The houses may have been small, dark and damp but they were well scrubbed and the inhabitants appeared to have some self respect. Diets as described by Sir William Temple in the first quarter of the 17th century were mostly “buttermilk boiled with apples, stockfish, buttered turnips and carrots, lettuce, salads and red herrings, washed down with small beer.” The English called the Dutch ‘butter boxes’ and the French called them ‘cheese balls’. They should have also called them frugal since the Dutch farmers were selling their high-quality butter and cheese for export and eating the cheapest butter and cheese which was imported from Ireland or the north of England.

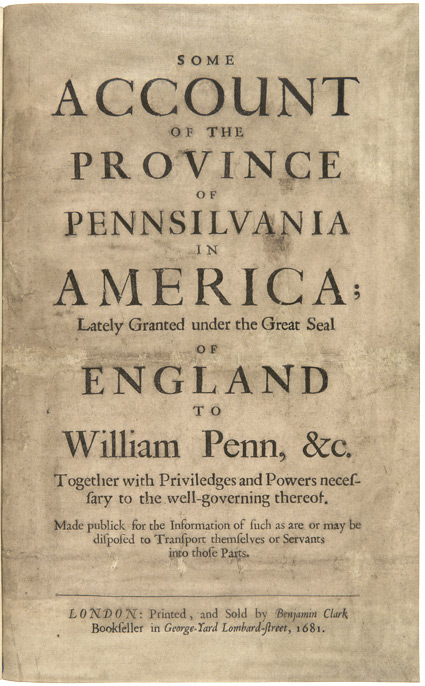

It is interesting to note that the family lived in the Netherlands at the time of that country’s greatest accomplishments. The start of the decline of that country as a shipping power came at just about the same time our family moved to Pennsylvania. We can speculate about the reasons for that move. If at this time they were still Mennonites, it might have involved the fact that the Mennonites were only granted full citizenship in 1672. This is actually only ten years before the family left the Netherlands. Regardless, the family must have seen one of the various ‘flyers’ that William Penn circulated in the Netherlands. It was entitled, “A Brief Account of the Province of Pennsylvania”. In it he says:

“But they that go must wisely count the Cost, For they must work themselves, or be able to employ others. A Winter goes before a Summer, and the first work will be Countrey Labour, to clear Ground, and raise Provision: other things by degrees.”

He then gives specific information about the cost of passage to Pennsylvania and advice as what the settlers should take with them:

“1st. The Passage for Men and Women is Five Pounds a head, for Children under Ten Years Fifty Shillings, Sucking Children Nothing. For Freight of Goods Forty Shillings per Tun; but one Chest to every Passenger Free.

2ly. The Goods fit to take with them for use or sale are all Utensils for Husbandry and Building, and House-hold-stuff; Also all sorts of things for Apparel, as Cloath, Stuffes, Linnen &c. Wherein all that desire may be more particularly informed by Phillip Ford, at the Hood and Scarf in Bow-lane in London.”

The emigrant is then told something of the conditions of his life and work after he reaches Pennsylvania. So definite is this prospectus that one feels sure it state the actual experience of many of the early settlers on the Delaware. The prospectus continues:

“Lastly, Being by the Mercy of God safely arrived; be it in October, Two Men may clear as much Ground for Corn as usually beings by the following Harvest about Twenty Quarters; In the mean time they must buy Corn, which they may have as aforesaid; and if they buy them two Cows, and two Breeding Sows, with what the Indians for a small matter will bring in, of Fowl, Fish and Venison (which is incredibly Cheapt, as a Fat Buck for Two Shillings) that and their industry will supply them. It is apprehended, that Fifteen Pounds stock for each Man (who is first well in Cloaths, and provided with fit working Tools for Himself) will (by the Blessing of God) carry him thither, and keep him, till his own Plantation will accommodate him. But all are most seriously cautioned, how they proceed in the disposal of themselves.”

The advertisement closes with the following which sounds amusing today but is really as practical advice as that concerning tools and stock.

“And it is further Advised, that all such as go would at least get the Permission, if not the good Liking of their near Relations; for that is both Natural and a Duty incumbent upon all: And by this means will natural Affection be preserved and a Friendly and Profitable Correspondence maintained between them. In all which God Almighty (who is the Salvation of the Ends of the Earth) Direct us, that His Blessings may attend our Honest Indeavors; and then the Consequence of all our Undertakings will be to the Glory of His Great Name and the true Happiness of Us and Our Posterity, Amen.—William Penn.”

So the star was in the west not the east and a wise man, Pieter Myers, followed it westward to the new world in July or August of 1682.

| Page last touched: | Send e-mail to: hsmyers@gmail.com |